My Team, My Friends, and a Racist Welcome

I grew up in Marion, Indiana. Even though I haven't lived there for over 30 years, I still call this Central Indiana town home. One of my favorite parts about growing up in Marion was the opportunity to play organized sports from a very young age - PAL Club basketball, T-ball, and flag football. But in Marion, basketball has always been and likely forever will be king! Hoosier Hysteria can be seen in all of its glory in Bill Green Athletic Arena. Even the water tower used to list all of the State Basketball Championships won reminding one and all of what was of ultimate importance. I often say that the most prominent tree in Marion was the basketball goal. Every block had at least two or three. It seemed as if every little girl and every little boy grew up dreaming of one day becoming a Marion Giant donning the purple and gold.

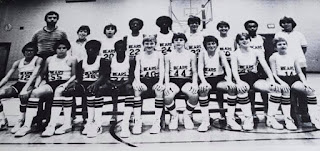

Before I got to Marion High School, I went to McCulloch Junior High from 1980 through 1983. Our mascot was the Bears, and our school colors were purple, gold, and white. I played center (I grew fast) for the Bears in seventh, eighth, and ninth grade. We were good. All three middle schools in Marion were. In fact, it seemed like the only games we would lose every year were the games we played against one another. I know that likely isn't true, but that's the story my 52 year old brain tells me. And I am sticking to it.

Every week in the late fall and winter, we would travel by bus throughout north central Indiana to play teams in Kokomo, Muncie, Anderson, Elwood, Gas City, and the likes. One of those trips from 1982 is emblazoned in my memory as if it happened yesterday. We were traveling to one of the smaller communities for an A game and a B game. We had so many guys on the team that playing two games insured that everyone would get to play. On the way, the bus was loud, and we were having a blast. Probably too much fun for our coach. He usually ignored us on our trips to and from our games as long as we kept our noise just below that of an airplane taking off. Occasionally, he would have enough. He would raise his gruff coach voice above the noise pleading us to bring it down a notch, and he would promise us more running at our next practice if we didn’t. His pleading didn’t often work, but his threat of running more always did.

Everything about the trip seemed like a normal journey until we got a little closer to our destination. Coach then had the bus slow down, and he proceeded to tell us that he needed to talk to us. The seriousness in his voice instantly changed the tone of the jovial bus and told us something was up. He called us closer to him. As we gathered near the front of the bus, he said, “Men, I need to tell you how we are going to get off of the bus once we get to the school.” I remember thinking that was such an odd thing to say. We had spent most of our lives getting on and off of buses. Why would this be any different? Coach went on to instruct us that we would be getting off in a formation. The coaches would get off first and last with the head coach at the front and the assistance coach at the back. I was told along with two of my other teammates that we were to be the first players off the bus. All three of us were tall and … well, white. The remaining White players were instructed to get off next. My Black teammates and friends, who represented more than half of the team, were then told to fill in the space behind and in between the White players. What an odd request. What a strange thing to be asked to do. We had never been told to do something like this before. And we didn’t have a clue as to why coach would ask us to do such a thing now. To say we were confused would be a huge understatement. We remained uncertain until the bus rounded the corner by the school. And there they were. Hundreds of White grown ups stood side by side lining the sidewalk all the way from the bus drop off zone to the locker room doors silently awaiting our arrival. Let me be clear, this was no welcoming committee. These stone faced silent sentinels gathered there to bully, to intimidate, to frighten a group of Black young men and their White teammates who were coming to play the game of basketball. We were there to play the game of basketball. And they wanted us to be sure; no, they wanted my Black teammates to be sure they knew they weren’t welcome there. They never had been, and they never would be.

We got off the bus exactly the way coach asked us to. And we walked in to the school wearing our sweaters and nice pants, carrying our duffle bags in our hands, our eyes focused straight ahead, and lumps firmly fixed in our throats. It was a long and scary walk. But I cannot imagine how long that trip was for my friends. I cannot imagine how frightened they were all the way in to the locker room. I cannot imagine how scared they must have been during warmups.

I don’t remember what happened during the game except that we won. I don’t remember if we ever talked about it as a team or even as friends. What I do remember is how afraid I was for myself and for my friends as we walked in to that gym.

But somehow, even then, I knew that I was ultimately safe. It wasn’t me the crowd had come for. The evil that is racism comes for Black bodies no matter what the obstacle.

Here is something else I know. My Black friends are still making that same damn walk every day of their lives. There are corridors and sidewalks and hallways and alleys and school yards and neighborhoods and streets and playgrounds and stores and communities and towns and minds in this country and around the world where they are not safe just because they are Black. Let that sink in. Read it again.

You want to know why people are filling the streets?

You want to know why people are angry?

You want to know why there isn’t any more time to wait?

You want to know why I will continue to say Black Lives Matter?

You want to know why I will put my body and my life on the line for the sake of Black people?

It’s because of that walk. Not the one I took when I was 14. No, the one that Black people take every single day of their lives. Lives are at risk. Black lives are at risk. Black Lives Matter.

(footnote: I tried to read this out loud to Jennifer before I posted it, and I wept. It is painful because it is still all too real. It is past time for change.)

Before I got to Marion High School, I went to McCulloch Junior High from 1980 through 1983. Our mascot was the Bears, and our school colors were purple, gold, and white. I played center (I grew fast) for the Bears in seventh, eighth, and ninth grade. We were good. All three middle schools in Marion were. In fact, it seemed like the only games we would lose every year were the games we played against one another. I know that likely isn't true, but that's the story my 52 year old brain tells me. And I am sticking to it.

Every week in the late fall and winter, we would travel by bus throughout north central Indiana to play teams in Kokomo, Muncie, Anderson, Elwood, Gas City, and the likes. One of those trips from 1982 is emblazoned in my memory as if it happened yesterday. We were traveling to one of the smaller communities for an A game and a B game. We had so many guys on the team that playing two games insured that everyone would get to play. On the way, the bus was loud, and we were having a blast. Probably too much fun for our coach. He usually ignored us on our trips to and from our games as long as we kept our noise just below that of an airplane taking off. Occasionally, he would have enough. He would raise his gruff coach voice above the noise pleading us to bring it down a notch, and he would promise us more running at our next practice if we didn’t. His pleading didn’t often work, but his threat of running more always did.

Everything about the trip seemed like a normal journey until we got a little closer to our destination. Coach then had the bus slow down, and he proceeded to tell us that he needed to talk to us. The seriousness in his voice instantly changed the tone of the jovial bus and told us something was up. He called us closer to him. As we gathered near the front of the bus, he said, “Men, I need to tell you how we are going to get off of the bus once we get to the school.” I remember thinking that was such an odd thing to say. We had spent most of our lives getting on and off of buses. Why would this be any different? Coach went on to instruct us that we would be getting off in a formation. The coaches would get off first and last with the head coach at the front and the assistance coach at the back. I was told along with two of my other teammates that we were to be the first players off the bus. All three of us were tall and … well, white. The remaining White players were instructed to get off next. My Black teammates and friends, who represented more than half of the team, were then told to fill in the space behind and in between the White players. What an odd request. What a strange thing to be asked to do. We had never been told to do something like this before. And we didn’t have a clue as to why coach would ask us to do such a thing now. To say we were confused would be a huge understatement. We remained uncertain until the bus rounded the corner by the school. And there they were. Hundreds of White grown ups stood side by side lining the sidewalk all the way from the bus drop off zone to the locker room doors silently awaiting our arrival. Let me be clear, this was no welcoming committee. These stone faced silent sentinels gathered there to bully, to intimidate, to frighten a group of Black young men and their White teammates who were coming to play the game of basketball. We were there to play the game of basketball. And they wanted us to be sure; no, they wanted my Black teammates to be sure they knew they weren’t welcome there. They never had been, and they never would be.

We got off the bus exactly the way coach asked us to. And we walked in to the school wearing our sweaters and nice pants, carrying our duffle bags in our hands, our eyes focused straight ahead, and lumps firmly fixed in our throats. It was a long and scary walk. But I cannot imagine how long that trip was for my friends. I cannot imagine how frightened they were all the way in to the locker room. I cannot imagine how scared they must have been during warmups.

I don’t remember what happened during the game except that we won. I don’t remember if we ever talked about it as a team or even as friends. What I do remember is how afraid I was for myself and for my friends as we walked in to that gym.

But somehow, even then, I knew that I was ultimately safe. It wasn’t me the crowd had come for. The evil that is racism comes for Black bodies no matter what the obstacle.

Here is something else I know. My Black friends are still making that same damn walk every day of their lives. There are corridors and sidewalks and hallways and alleys and school yards and neighborhoods and streets and playgrounds and stores and communities and towns and minds in this country and around the world where they are not safe just because they are Black. Let that sink in. Read it again.

You want to know why people are filling the streets?

You want to know why people are angry?

You want to know why there isn’t any more time to wait?

You want to know why I will continue to say Black Lives Matter?

You want to know why I will put my body and my life on the line for the sake of Black people?

It’s because of that walk. Not the one I took when I was 14. No, the one that Black people take every single day of their lives. Lives are at risk. Black lives are at risk. Black Lives Matter.

(footnote: I tried to read this out loud to Jennifer before I posted it, and I wept. It is painful because it is still all too real. It is past time for change.)

Comments

Post a Comment